The Drawbridge Mentality—Exclusion and Escapism in Acton, Massachusetts

BY THE REPORTING TEAM

|

Part 1: Community Conversations

It's a wintry Thursday in the last week of January, in a grand room on the second floor of Town Hall. Posters are spaced evenly around the brightly-lit room, featuring colorful charts paired with questions such as “What demographic trends surprised you?” or “Where should new housing be built?” Staffers direct each attendee to pick up a pen and a stack of sticky notes, creating an English class-like atmosphere. Tonight’s public forum seeks to inform the Housing Production Plan (HPP). The visioning document will detail how Acton plans to meet its obligations under state law to ensure a supply of affordable housing. The town has advertised this forum for weeks, including a press release in the Boston Globe. Those efforts have brought out a crowd of sixty-five participants, many of whom were regulars at local political events and committees. For most attendees however, attending hearings on housing policy was an infrequent affair; one resident prefaced his interview by noting that he was “not a very informed person” on housing issues. |

A poster soliciting opinions at the January 30th Housing Production Plan forum.

|

The town provided educational resources for the general public, including a handy glossary of terms, but much of the discussion was detached and technical—the hot button issue concerned how to place deed restrictions on existing condominiums. For some in the audience, the issue held more emotional significance—one woman attended because she wanted “to see what are the ways that I can continue to stay” in Acton.

Halfway across town, another public forum was organized on shorter notice. One-hundred and sixty students, parents, and community members filed into the high school auditorium to convene a community conversation after an African American mother was arrested in an incident at Merriam that most attendees considered an act of racial profiling.

After the superintendent reiterated his intent to listen, the first to take the microphone was Maribel Mendoza, a mother of two, a business owner, and the first in a long line of speakers that night to tell their stories, about how they or their children had experienced acts of racism in the school community.

“Acton's not immune to anything. I've experienced racism in Dallas, and in Minnesota, and a lot of other places.” recounted Mendoza. “The fact that it exists here—I think we can just stop tiptoeing around it, and say we’re in a perfect little bubble of Acton, and it doesn't exist here—because it does...I was saddened [by watching the video of the encounter], but then it turned to fear, a real fear.”

“[I]n Acton, we are a diverse community, but we're not.” continued Ms. Mendoza, “And you know, especially for African Americans and Latinos, we’re the tiniest portion of this community.”

While Acton’s Asian-American population has expanded greatly over the last few decades, the latest estimates from the Census Bureau lists Hispanics as 3.1% of the population and African Americans at a mere 1.7%. [1] The natural next question is why? The Spectrum has encountered various theories as to why Acton’s Black and Latino communities are disproportionately small, from the lack of industry in town to the lack of other minority neighbors and the idea that people want to “live with their own kind.” But one particularly compelling theory points to the regulation of our housing stock.

Since the turn of the 20th century, when African Americans flocked north in “the Great Migration,” various public and private institutions have sought to exclude minority groups, particularly African Americans, from predominantly white neighborhoods and suburbs. From redlining by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to racial steering by realtors, the overall effect was disinvestment.

“Economic zoning” restricting multi-family developments proliferated in cities in the 1910s, and in suburbs in the ensuing decades, at least in part to exclude low-income minorities from wealthier neighborhoods. The postwar suburbanization of the 1950s, which transformed Acton from an agricultural village to a bedroom community, had a similar effect. As Acton’s population quadrupled in the 1950s and 1960s, residents grew more concerned about the pace of development. These concerns, regardless of their intentions, had the effect of restricting the housing supply The resulting shortage of affordable housing in Acton and similar towns across the state created an impetus for state intervention, for the legislature to create Chapter 40B in 1969. Chapter 40B calls on each municipality to set aside 10% of its housing stock for affordable units. To enforce this, 40B allows developers to override local regulations and red tape on projects contributing towards that goal.

40B has helped to create tens of thousands of units of affordable and market-rate housing. However, in the years since 1969, Boston’s housing crisis has worsened, and its suburbs are as exclusive as ever.

In the past two decades, Acton has made significant progress on its 40B obligations, notably with the construction of Avalon in 2006. If the town follows through on the Housing Production Plan it released last month, it will be on track to fulfill the requirement in Chapter 40B to have 10% of its housing be designated “affordable.”

This represents a tremendous milestone, but achieving racial and economic inclusivity will require considering a broader set of stakeholders. As The Spectrum wrote about last spring, the Acton of today has embraced its growing Asian American population, and taken pride in its cultural diversity. But as the meeting at the high school demonstrated powerfully, many residents still feel excluded from the town’s narrative.

Narratives of racism often center on the virulent actions of a few prejudicial citizens and officials. But looking at the suburbs around Route 128, a state commission concluded in 1975 that “[i]t is not the bigots, however, who constitute the primary obstructive force against racial inclusion. It is the indifference of average citizens.”

Absent the pressures of Chapter 40B, Acton will need to be even more deliberate if it seeks to ensure the town is open to all. It will need to balance a variety of goals and perspectives to live up to its stated ideals. It will require the continuation of conversations about diversity and development that Acton has been having for the past seventy years.

Part 2: "Rural Character"

The town of Acton was not always a bedroom community. Until the end of World War II, Acton was a tight-knit rural community with few commuters despite having a stop on the commuter rail.

Speaking as part of the town’s bicentennial in 1976, longtime residents Stuart Kennedy and Katherine Kinsey recounted the town’s evolution from a time when “everyone was a farmer, or connected with farming.”

Kennedy’s narrative of Acton’s transformation started after the first World War when the town’s young men “went into Boston or into local industry” rather than return to the family farm. As the older generation gradually retired, “[t]he developers went out and bought [their] farms...and that's what started the building [of] this town.”

Kennedy and Kinsey also recalled a darker period in Acton’s history, during the depths of the Great Depression.

Miss Kinsley tells us,

Halfway across town, another public forum was organized on shorter notice. One-hundred and sixty students, parents, and community members filed into the high school auditorium to convene a community conversation after an African American mother was arrested in an incident at Merriam that most attendees considered an act of racial profiling.

After the superintendent reiterated his intent to listen, the first to take the microphone was Maribel Mendoza, a mother of two, a business owner, and the first in a long line of speakers that night to tell their stories, about how they or their children had experienced acts of racism in the school community.

“Acton's not immune to anything. I've experienced racism in Dallas, and in Minnesota, and a lot of other places.” recounted Mendoza. “The fact that it exists here—I think we can just stop tiptoeing around it, and say we’re in a perfect little bubble of Acton, and it doesn't exist here—because it does...I was saddened [by watching the video of the encounter], but then it turned to fear, a real fear.”

“[I]n Acton, we are a diverse community, but we're not.” continued Ms. Mendoza, “And you know, especially for African Americans and Latinos, we’re the tiniest portion of this community.”

While Acton’s Asian-American population has expanded greatly over the last few decades, the latest estimates from the Census Bureau lists Hispanics as 3.1% of the population and African Americans at a mere 1.7%. [1] The natural next question is why? The Spectrum has encountered various theories as to why Acton’s Black and Latino communities are disproportionately small, from the lack of industry in town to the lack of other minority neighbors and the idea that people want to “live with their own kind.” But one particularly compelling theory points to the regulation of our housing stock.

Since the turn of the 20th century, when African Americans flocked north in “the Great Migration,” various public and private institutions have sought to exclude minority groups, particularly African Americans, from predominantly white neighborhoods and suburbs. From redlining by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to racial steering by realtors, the overall effect was disinvestment.

“Economic zoning” restricting multi-family developments proliferated in cities in the 1910s, and in suburbs in the ensuing decades, at least in part to exclude low-income minorities from wealthier neighborhoods. The postwar suburbanization of the 1950s, which transformed Acton from an agricultural village to a bedroom community, had a similar effect. As Acton’s population quadrupled in the 1950s and 1960s, residents grew more concerned about the pace of development. These concerns, regardless of their intentions, had the effect of restricting the housing supply The resulting shortage of affordable housing in Acton and similar towns across the state created an impetus for state intervention, for the legislature to create Chapter 40B in 1969. Chapter 40B calls on each municipality to set aside 10% of its housing stock for affordable units. To enforce this, 40B allows developers to override local regulations and red tape on projects contributing towards that goal.

40B has helped to create tens of thousands of units of affordable and market-rate housing. However, in the years since 1969, Boston’s housing crisis has worsened, and its suburbs are as exclusive as ever.

In the past two decades, Acton has made significant progress on its 40B obligations, notably with the construction of Avalon in 2006. If the town follows through on the Housing Production Plan it released last month, it will be on track to fulfill the requirement in Chapter 40B to have 10% of its housing be designated “affordable.”

This represents a tremendous milestone, but achieving racial and economic inclusivity will require considering a broader set of stakeholders. As The Spectrum wrote about last spring, the Acton of today has embraced its growing Asian American population, and taken pride in its cultural diversity. But as the meeting at the high school demonstrated powerfully, many residents still feel excluded from the town’s narrative.

Narratives of racism often center on the virulent actions of a few prejudicial citizens and officials. But looking at the suburbs around Route 128, a state commission concluded in 1975 that “[i]t is not the bigots, however, who constitute the primary obstructive force against racial inclusion. It is the indifference of average citizens.”

Absent the pressures of Chapter 40B, Acton will need to be even more deliberate if it seeks to ensure the town is open to all. It will need to balance a variety of goals and perspectives to live up to its stated ideals. It will require the continuation of conversations about diversity and development that Acton has been having for the past seventy years.

Part 2: "Rural Character"

The town of Acton was not always a bedroom community. Until the end of World War II, Acton was a tight-knit rural community with few commuters despite having a stop on the commuter rail.

Speaking as part of the town’s bicentennial in 1976, longtime residents Stuart Kennedy and Katherine Kinsey recounted the town’s evolution from a time when “everyone was a farmer, or connected with farming.”

Kennedy’s narrative of Acton’s transformation started after the first World War when the town’s young men “went into Boston or into local industry” rather than return to the family farm. As the older generation gradually retired, “[t]he developers went out and bought [their] farms...and that's what started the building [of] this town.”

Kennedy and Kinsey also recalled a darker period in Acton’s history, during the depths of the Great Depression.

Miss Kinsley tells us,

I can remember when the Ku Klux Klan was very strong here, in the thirties, the depression years. Nobody talked about it, but on a moonlit night you could sense something; the village was small. There were daring young men in town who followed them to find out who was behind the white sheets.

There was a very fine Jewish gentleman in South Acton... he and his brother owned a mill. They burned a cross across from his house... and that was terrible. Nobody knew what was going to happen.

Mr. Kennedy calls Acton the “hotbed” of Ku Klux Klan activities in this part of New England during those depression years.

***

As the country came out of the Depression and the Second World War, Acton was transformed by the rising tide of post-war prosperity. The town population doubled in the 1950s and again in the 1960s, nearing 15,000 by 1970.

Much of this expansion and migration can be attributed to the innovative companies around Route 128. These included Maynard-based Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), a pioneer in the minicomputer industry whose revenues topped 3.2 billion at their peak in 1981. [2]

As Route 128 earned the title of “America’s Technology Highway,” Acton became highly attractive to families looking for a good school and a modest commute at a reasonable price. As David Green, who moved to Acton as a child in the 1970s before returning to teach at ABRHS, told The Spectrum in the first part of this series last year, “it’s horrible to say, but [Acton] was [a] good bang for the buck. It was really good bang for the buck.”

These new suburbanites were highly educated–and at that time overwhelmingly white. The Massachusetts Commission against Discrimination. A 1975 report prepared for the US Commission on Civil Rights by a joint state-federal commission described how “[w]hile the major Black migration into the Boston area occurred almost simultaneously with the rapid buildup of the 128 suburbs, neither the indigenous Black population of Boston nor the incoming Blacks participated in the expanded housing and employment market beyond the city.”

Route 128 became a prime example of the white flight and suburban sprawl that played out across the country in the postwar period. The report found that, by the early 1960s, 80% of the whites in Greater Boston lived in suburban areas, while 80% of its Black population was clustered in central parts of the city.

Activists and civic leaders in and around Acton sought to rectify these demographic imbalances. For example, two of Acton’s clergymen, Dean Lancier and Roger Wooten, attended the 1963 March on Washington and pushed for inclusivity back home.

“Some of the real estate people in town grew very alarmed when they saw a Black family that came and were looking,” recounted Wooten to WGBH’s Phillip Martin in a 2013 interview, “We would bring some pressure to bear against any resistance from the real estate people.”

Despite the best efforts of Wooten and others, some African Americans chose not to become “pioneers” in a town with a Black population in the single digits. An article in the Assabet Valley Beacon on June 6 1968 reported that:

***

As the country came out of the Depression and the Second World War, Acton was transformed by the rising tide of post-war prosperity. The town population doubled in the 1950s and again in the 1960s, nearing 15,000 by 1970.

Much of this expansion and migration can be attributed to the innovative companies around Route 128. These included Maynard-based Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), a pioneer in the minicomputer industry whose revenues topped 3.2 billion at their peak in 1981. [2]

As Route 128 earned the title of “America’s Technology Highway,” Acton became highly attractive to families looking for a good school and a modest commute at a reasonable price. As David Green, who moved to Acton as a child in the 1970s before returning to teach at ABRHS, told The Spectrum in the first part of this series last year, “it’s horrible to say, but [Acton] was [a] good bang for the buck. It was really good bang for the buck.”

These new suburbanites were highly educated–and at that time overwhelmingly white. The Massachusetts Commission against Discrimination. A 1975 report prepared for the US Commission on Civil Rights by a joint state-federal commission described how “[w]hile the major Black migration into the Boston area occurred almost simultaneously with the rapid buildup of the 128 suburbs, neither the indigenous Black population of Boston nor the incoming Blacks participated in the expanded housing and employment market beyond the city.”

Route 128 became a prime example of the white flight and suburban sprawl that played out across the country in the postwar period. The report found that, by the early 1960s, 80% of the whites in Greater Boston lived in suburban areas, while 80% of its Black population was clustered in central parts of the city.

Activists and civic leaders in and around Acton sought to rectify these demographic imbalances. For example, two of Acton’s clergymen, Dean Lancier and Roger Wooten, attended the 1963 March on Washington and pushed for inclusivity back home.

“Some of the real estate people in town grew very alarmed when they saw a Black family that came and were looking,” recounted Wooten to WGBH’s Phillip Martin in a 2013 interview, “We would bring some pressure to bear against any resistance from the real estate people.”

Despite the best efforts of Wooten and others, some African Americans chose not to become “pioneers” in a town with a Black population in the single digits. An article in the Assabet Valley Beacon on June 6 1968 reported that:

Last month in an open meeting probing suburban response to [the Kerner Commission report on the 1967 race riots], the following statement by a realtor shocked some members of the audience. He stated, “I have a Black man interested in buying a house in this area. But, he may decide not to buy here, because he is afraid.

The racial steering Wooten described likely helped to deter potential residents of color. Wooten describes. [3] Others may have been intimidated by the prospect of being one of the few Black residents in a white town. But affordability has always constituted one of the primary barriers to racial homogeneity.

Acton created its first zoning bylaw in 1953, but it was relatively lax throughout the 1950s and 1960s. However, as Acton continued to grow, many residents became increasingly concerned about the growth of the town, and sought to constrain it. This was particularly the case around multi-family housing. In his case study on Acton’s development, Harvard researcher Alex Von Hoffman traces how Acton initially accommodated the high demand for apartments in the area, processing as many as 300 apartment permits a year in 1968. But as apartments sprung up in the lightly-regulated business and industrial districts, Acton became “an early member of the movement against multifamily buildings” which spread throughout the Boston metro area in the late 1960s and 1970s. Von Hoffman writes that residents considered the new apartments “large” and “unsightly.” Voters gradually restricted the building of apartments at Town Meeting—banning them from industrial districts in 1968, and requiring Selectman approval in 1971—until apartment permitting had more or less ceased by 1975. [4] [5]

Under the laissez-faire regime, planners projected in 1961 that Acton would one day contain between 40,000 and 45,000 residents. [6] But with apartment restrictions, minimum acreage requirements, and other regulatory constraints in place, the tide of development slowed to a trickle.

MAP OF HOUSING DEVELOPMENT OVER TIME

Acton created its first zoning bylaw in 1953, but it was relatively lax throughout the 1950s and 1960s. However, as Acton continued to grow, many residents became increasingly concerned about the growth of the town, and sought to constrain it. This was particularly the case around multi-family housing. In his case study on Acton’s development, Harvard researcher Alex Von Hoffman traces how Acton initially accommodated the high demand for apartments in the area, processing as many as 300 apartment permits a year in 1968. But as apartments sprung up in the lightly-regulated business and industrial districts, Acton became “an early member of the movement against multifamily buildings” which spread throughout the Boston metro area in the late 1960s and 1970s. Von Hoffman writes that residents considered the new apartments “large” and “unsightly.” Voters gradually restricted the building of apartments at Town Meeting—banning them from industrial districts in 1968, and requiring Selectman approval in 1971—until apartment permitting had more or less ceased by 1975. [4] [5]

Under the laissez-faire regime, planners projected in 1961 that Acton would one day contain between 40,000 and 45,000 residents. [6] But with apartment restrictions, minimum acreage requirements, and other regulatory constraints in place, the tide of development slowed to a trickle.

MAP OF HOUSING DEVELOPMENT OVER TIME

Source: Data from Acton Assessor’s Office

The arguments behind these policies were varied. Von Hoffman found that “Actonians’ revulsion to development focused on issues like environmental conservation and septic capacity, and especially on their desire to retain the town’s ‘rural character.’” But regardless of the reasons behind them, recently retired town planner Roland Bartl noted that these policies “had at least the effect of increasing the value of land and making it harder for people with low income to find opportunity for housing in the town.

And a lot of communities were doing it” Bartl pointed out, “not just Acton.”

Part 3: A Brief History of Housing Segregation

In a brazen act of segregation, the city of Baltimore passed a zoning ordinance in 1910 that prevented Black homebuyers from purchasing homes on majority-white city blocks (and vice versa). Other Southern cities soon followed suit, as did some Northern and Mid-Atlantic municipalities responding to an influx of Black residents during the early stages of the Great Migration, where many African-Americans moved north to escape social and economic oppression in the Deep South.

Racial zoning laws proliferated until a landmark Supreme Court case in 1918. Drawing on libertarian principles of property rights, the Court unanimously decided in Buchanan v. Warley that racial zoning ordinances violated the due protection clause of the 14th Amendment. W.E.B. Debois famously credited Buchanan with breaking “the backbone of segregation,” while some contemporary scholars like George Mason University’s David Bernstein credit the case with helping the United States avert the worst features of South-African apartheid. But the Buchanan decision failed to stem the tide of segregation. For one, the case’s focus on property rights failed to address other prevalent forms of racial segregation. Further still, Buchanan only applied to public policy, so in many places private, racially-restrictive housing covenants soon replaced official ordinances as a means to create single-race neighborhoods.

Landowners and developers included these covenants in a property’s deed, which were legally enforceable on future owners. They prohibited the sale or occupation of the property to members of certain groups, mostly African Americans, and they were enforced as private contracts by real estate boards and neighborhood associations.

In cities like Chicago and Los Angeles, as much as 80% of property carried covenants restricting their sale to or occupation by African Americans by 1940, according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Covenants often declared that “hereafter no part of said property or any portion thereof shall be…occupied by any person not of the Caucasian race, it being intended hereby to restrict the use of said property…against occupancy as owners or tenants of any portion of said property for resident or other purposes by people of the Negro or Mongolian race.”

Explicit racial exclusion in the form of racial covenants was often combined with subtler forms of exclusion such as racial steering, blockbusting, and simple social isolation. Racial steering was the focus of Lorraine Hansberry’s famous play A Raisin in The Sun, where a neighborhood association seeks to dissuade and intimidate an African American family from moving into their all-white neighborhood. Steering of this sort was complemented by blockbusting: once a Black family moved into the neighborhood, realtors would fan out to tell white residents that racial integration was imminent, and that it would cause their property values to plummet. These realtors would then buy these homes from whites owners and sell them to Black families for immense profits.

Racially exclusionary policies such as restrictive covenants and racial steering were often justified and promoted as a means of preserving property values. This doctrine—that property values depended on maintaining a neighborhood’s social character--was an unchallenged assumption throughout the housing industry. From 1924 to 1950, the National Association of Real Estate Boards code of conduct stipulated that “[a] Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.” Textbooks reinforced a realtor’s ethical obligation to promote neighborhood homogeneity.

The same self-fulfilling assumption—that integration lowered property values—drove federal policy as well, in what came to be known as redlining. Amidst a great economic crisis that arrested a decade’s worth of prosperity, the federal government began a housing loan program as part of the Depression-era New Deal designed to increase the quality of housing supply. The widespread destitution caused by the Depression prevented the majority of Americans from buying new homes and pushed others out of their houses via forced foreclosure. The housing market needed stability for these Americans to pursue homeownership again. One New Deal institution, the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), sought to manufacture this stability by insuring mortgages issued by qualifying lenders, as many banks, now destitute due to the financial crisis, relied on the stimulus of mortgages to sustain themselves. By insuring a mortgage, the FHA assumed the risk of people defaulting on loan payments, meaning the banks were not losing the stimulus they required when people couldn’t afford their mortgage. FHA guarantees made banks comfortable lending to ordinary people, increasing the proportion of Americans who could afford to buy homes as the FHA increased the maximum mortgage loan.

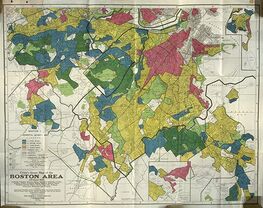

While this action had an overtly positive connotation, the implicit biases of the officials tasked with managing the FHA in combination with the subjective nature of the FHA’s practices resulted in a federally-sanctioned racial-segregation campaign—redlining. According to the Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston, redlining “is the practice of denying or limiting financial services to certain neighborhoods based on racial or ethnic composition without regard to the residents’ qualifications or creditworthiness,” effectively demarcating white and Black racial neighborhoods. The FHA had clear indications of bias, implying that white homeowners were less of a credit risk, regardless of past credit history, and that predominantly Black neighborhoods contained “inharmonious racial or nationality groups.” The FHA relied on the Underwriting Handbook to determine a property/property-owner’s eligibility for an FHA loan, and appraisers with the Home Owner’s Loan Coalition (HOLC) created residential security maps to be incorporated into the handbook. These residential security maps were color-coded to indicate the security of a mortgage in a certain neighborhood of 239 cities in America, designation based solely on assumptions of the community as opposed to the individual creditworthiness of each household. [7]

And a lot of communities were doing it” Bartl pointed out, “not just Acton.”

Part 3: A Brief History of Housing Segregation

In a brazen act of segregation, the city of Baltimore passed a zoning ordinance in 1910 that prevented Black homebuyers from purchasing homes on majority-white city blocks (and vice versa). Other Southern cities soon followed suit, as did some Northern and Mid-Atlantic municipalities responding to an influx of Black residents during the early stages of the Great Migration, where many African-Americans moved north to escape social and economic oppression in the Deep South.

Racial zoning laws proliferated until a landmark Supreme Court case in 1918. Drawing on libertarian principles of property rights, the Court unanimously decided in Buchanan v. Warley that racial zoning ordinances violated the due protection clause of the 14th Amendment. W.E.B. Debois famously credited Buchanan with breaking “the backbone of segregation,” while some contemporary scholars like George Mason University’s David Bernstein credit the case with helping the United States avert the worst features of South-African apartheid. But the Buchanan decision failed to stem the tide of segregation. For one, the case’s focus on property rights failed to address other prevalent forms of racial segregation. Further still, Buchanan only applied to public policy, so in many places private, racially-restrictive housing covenants soon replaced official ordinances as a means to create single-race neighborhoods.

Landowners and developers included these covenants in a property’s deed, which were legally enforceable on future owners. They prohibited the sale or occupation of the property to members of certain groups, mostly African Americans, and they were enforced as private contracts by real estate boards and neighborhood associations.

In cities like Chicago and Los Angeles, as much as 80% of property carried covenants restricting their sale to or occupation by African Americans by 1940, according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Covenants often declared that “hereafter no part of said property or any portion thereof shall be…occupied by any person not of the Caucasian race, it being intended hereby to restrict the use of said property…against occupancy as owners or tenants of any portion of said property for resident or other purposes by people of the Negro or Mongolian race.”

Explicit racial exclusion in the form of racial covenants was often combined with subtler forms of exclusion such as racial steering, blockbusting, and simple social isolation. Racial steering was the focus of Lorraine Hansberry’s famous play A Raisin in The Sun, where a neighborhood association seeks to dissuade and intimidate an African American family from moving into their all-white neighborhood. Steering of this sort was complemented by blockbusting: once a Black family moved into the neighborhood, realtors would fan out to tell white residents that racial integration was imminent, and that it would cause their property values to plummet. These realtors would then buy these homes from whites owners and sell them to Black families for immense profits.

Racially exclusionary policies such as restrictive covenants and racial steering were often justified and promoted as a means of preserving property values. This doctrine—that property values depended on maintaining a neighborhood’s social character--was an unchallenged assumption throughout the housing industry. From 1924 to 1950, the National Association of Real Estate Boards code of conduct stipulated that “[a] Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood.” Textbooks reinforced a realtor’s ethical obligation to promote neighborhood homogeneity.

The same self-fulfilling assumption—that integration lowered property values—drove federal policy as well, in what came to be known as redlining. Amidst a great economic crisis that arrested a decade’s worth of prosperity, the federal government began a housing loan program as part of the Depression-era New Deal designed to increase the quality of housing supply. The widespread destitution caused by the Depression prevented the majority of Americans from buying new homes and pushed others out of their houses via forced foreclosure. The housing market needed stability for these Americans to pursue homeownership again. One New Deal institution, the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), sought to manufacture this stability by insuring mortgages issued by qualifying lenders, as many banks, now destitute due to the financial crisis, relied on the stimulus of mortgages to sustain themselves. By insuring a mortgage, the FHA assumed the risk of people defaulting on loan payments, meaning the banks were not losing the stimulus they required when people couldn’t afford their mortgage. FHA guarantees made banks comfortable lending to ordinary people, increasing the proportion of Americans who could afford to buy homes as the FHA increased the maximum mortgage loan.

While this action had an overtly positive connotation, the implicit biases of the officials tasked with managing the FHA in combination with the subjective nature of the FHA’s practices resulted in a federally-sanctioned racial-segregation campaign—redlining. According to the Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston, redlining “is the practice of denying or limiting financial services to certain neighborhoods based on racial or ethnic composition without regard to the residents’ qualifications or creditworthiness,” effectively demarcating white and Black racial neighborhoods. The FHA had clear indications of bias, implying that white homeowners were less of a credit risk, regardless of past credit history, and that predominantly Black neighborhoods contained “inharmonious racial or nationality groups.” The FHA relied on the Underwriting Handbook to determine a property/property-owner’s eligibility for an FHA loan, and appraisers with the Home Owner’s Loan Coalition (HOLC) created residential security maps to be incorporated into the handbook. These residential security maps were color-coded to indicate the security of a mortgage in a certain neighborhood of 239 cities in America, designation based solely on assumptions of the community as opposed to the individual creditworthiness of each household. [7]

|

Based on the HOLC maps, the FHA also refused to provide older residential neighborhoods in inner cities, citing the riskiness of loans meant for renovation of older homes. This has a double-pronged effect: not only did it lead to the neglect of inner-city areas, which had drawn a large proportion of Black Americans during the Great Migration, but it also promoted the disintegration of the urban middle class in the inner cities. The middle class could afford to purchase new homes on the fringes of the city because the FHA was not only more keen to provide insurance to the new residential communities springing up on the outskirts of cities, but the generosity of loans for white Americans made this a feasible option. By the end of World War II, white Americans began to occupy the suburbs, and Black Americans were denied the opportunity to join them.

|

Source: The "Stuff You Missed in History Class" podcast

|

The FHA was one great contributor to the phenomenon that became known as “white flight”: the mass emigration of the white middle class out from the cities and into what would become the suburbs of America’s cities. In addition to the legal exclusion of Black Americans from these suburbs, the construction of the Interstate Highway System under Eisenhower after World War II, physically separated neighborhoods of differing racial composition, and especially in the Deep South, the layout of the interstates created resource deserts targeting Black neighborhoods. [8] Governments subsidized white flight by allocating tax revenue to the development of these new, burgeoning municipalities to avoid incurring the “legacy costs” of continuing to develop and maintain the existing infrastructure of cities. The resulting urban disinvestment demonstrated clear prioritization of the new white neighborhoods and gross neglect of the existing urban ones to which Black Americans were legally confined. That the United States has become such a suburban country speaks volumes towards urban neglect and socioeconomic stratification in the cities.

Part 4: "Mere Parasites"

As a result of these historical inequities, African American families have accumulated much less wealth than white families over the past century. Homeownership accounts for two-thirds of the wealth held by the median American family, so the inability of African Americans to purchase a home in the 1930s left them unable to capitalize when home prices rose in the 1970s. A Brandeis University report identified “years of homeownership” as the best predictor of the wealth gap between white and African American families. And when the Federal Reserve examined the net worth of Boston’s households in 2015, it found that the median white household was worth $247,500, and the median Black household was worth $8. Not $8,000—$8.

Many activists and scholars point to this “wealth gap” to argue that low-density zoning, and the resulting shortages of affordable and multifamily housing, have a direct effect on a municipality’s racial composition. A variety of studies have established a correlation between racial homogeneity and low-density zoning, while Boston University researcher Matthew Ressenger went a step further in 2016 by looking at housing on the boundaries between more-restrictive and less-restrictive zoning districts. Ressenger concluded that “over half the difference between levels of segregation in the stringently zoned Boston and lightly zoned Houston metro areas can be explained by zoning regulation alone.”

Zoning proliferated in American cities during the Progressive Era. From the very start, cities adopted zoning as a means of racial and economic exclusion. The first Southern ordinances were explicitly racialized, and while racial zoning was outlawed in Buchanan, planners continued to attempt it for years after the Court’s decision.

In place of explicit racial zoning, some Southern cities turned to restrictive covenants, while others turned to “economic zoning” based on wealth, with backing from segregationists in the federal government. As Richard Rothstein writes in his 2015 book The Color of Law, “[t]o prevent lower-income African Americans from living in neighborhoods where middle-class whites resided, local and federal officials began … to promote zoning ordinances to reserve middle-class neighborhoods for single-family homes that lower-income families of all races could not afford.”

This was a page from the Northern playbook, where cities implemented zoning not only to exclude undesirable land use from upscale neighborhoods, but also to exclude undesirable people. Urban planner Yale Rabin writes that “[w]hat began as a means of improving the blighted physical environment in which people lived and worked [became] a mechanism for protecting property values and excluding the undesirables," such as immigrants and African Americans. In 1916, wealthy New York City residents pleaded with the city to protect their upscale section of Fifth Avenue from the loft buildings and immigrants of the nearby garment district. The lobbying effort that resulted produced the first comprehensive zoning ordinance in American history.

The desire for social class homogeneity was not unique to the city. According to a 2004 paper from Dartmouth professor William Fischel, as buses and trucks allowed heavy industry to move away from railroads and dockheads in the 1920s, suburban residents began pushing for zoning, both out of an attempt to preserve the exclusive and secluded nature of the community (often a selling point for developers) and to preserve property values from the perceived threat of tenement housing and economic integration. The 1926 Supreme Court case Euclid v. Ambler, the landmark case affirming the legality of zoning, centered around Euclid Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland. In the Court’s majority opinion, Justice George Sutherland explained how “very often the apartment house is a mere parasite, constructed in order to take advantage of the open spaces and attractive surroundings created by the residential character of the district.”

Zoning was ubiquitous in the suburbs by the 1950s, but home prices didn’t rise significantly until the 1970s. Fischel cites a couple factors which increased the salience of exclusionary attitudes. The development of interstate highways in the decades after World War II moved many jobs away from the urban center, and made quality of life more important than commuting distance. Meanwhile, civil rights laws actively sought to move minority residents into the suburbs. The rise of the environmentalist movement of the 1970s also helped to catalyze the opposition to denser development, because many environmental protection laws allowed a minority of neighbors to impede a development, even if it had majority support. Again referring to environmental conservation, As noted earlier, environmentalist rhetoric played a key role in Acton’s historical debates about housing development, and furthermore, that the resulting policies had the effect—intentional or not—of keeping people out.

Part 4: "Mere Parasites"

As a result of these historical inequities, African American families have accumulated much less wealth than white families over the past century. Homeownership accounts for two-thirds of the wealth held by the median American family, so the inability of African Americans to purchase a home in the 1930s left them unable to capitalize when home prices rose in the 1970s. A Brandeis University report identified “years of homeownership” as the best predictor of the wealth gap between white and African American families. And when the Federal Reserve examined the net worth of Boston’s households in 2015, it found that the median white household was worth $247,500, and the median Black household was worth $8. Not $8,000—$8.

Many activists and scholars point to this “wealth gap” to argue that low-density zoning, and the resulting shortages of affordable and multifamily housing, have a direct effect on a municipality’s racial composition. A variety of studies have established a correlation between racial homogeneity and low-density zoning, while Boston University researcher Matthew Ressenger went a step further in 2016 by looking at housing on the boundaries between more-restrictive and less-restrictive zoning districts. Ressenger concluded that “over half the difference between levels of segregation in the stringently zoned Boston and lightly zoned Houston metro areas can be explained by zoning regulation alone.”

Zoning proliferated in American cities during the Progressive Era. From the very start, cities adopted zoning as a means of racial and economic exclusion. The first Southern ordinances were explicitly racialized, and while racial zoning was outlawed in Buchanan, planners continued to attempt it for years after the Court’s decision.

In place of explicit racial zoning, some Southern cities turned to restrictive covenants, while others turned to “economic zoning” based on wealth, with backing from segregationists in the federal government. As Richard Rothstein writes in his 2015 book The Color of Law, “[t]o prevent lower-income African Americans from living in neighborhoods where middle-class whites resided, local and federal officials began … to promote zoning ordinances to reserve middle-class neighborhoods for single-family homes that lower-income families of all races could not afford.”

This was a page from the Northern playbook, where cities implemented zoning not only to exclude undesirable land use from upscale neighborhoods, but also to exclude undesirable people. Urban planner Yale Rabin writes that “[w]hat began as a means of improving the blighted physical environment in which people lived and worked [became] a mechanism for protecting property values and excluding the undesirables," such as immigrants and African Americans. In 1916, wealthy New York City residents pleaded with the city to protect their upscale section of Fifth Avenue from the loft buildings and immigrants of the nearby garment district. The lobbying effort that resulted produced the first comprehensive zoning ordinance in American history.

The desire for social class homogeneity was not unique to the city. According to a 2004 paper from Dartmouth professor William Fischel, as buses and trucks allowed heavy industry to move away from railroads and dockheads in the 1920s, suburban residents began pushing for zoning, both out of an attempt to preserve the exclusive and secluded nature of the community (often a selling point for developers) and to preserve property values from the perceived threat of tenement housing and economic integration. The 1926 Supreme Court case Euclid v. Ambler, the landmark case affirming the legality of zoning, centered around Euclid Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland. In the Court’s majority opinion, Justice George Sutherland explained how “very often the apartment house is a mere parasite, constructed in order to take advantage of the open spaces and attractive surroundings created by the residential character of the district.”

Zoning was ubiquitous in the suburbs by the 1950s, but home prices didn’t rise significantly until the 1970s. Fischel cites a couple factors which increased the salience of exclusionary attitudes. The development of interstate highways in the decades after World War II moved many jobs away from the urban center, and made quality of life more important than commuting distance. Meanwhile, civil rights laws actively sought to move minority residents into the suburbs. The rise of the environmentalist movement of the 1970s also helped to catalyze the opposition to denser development, because many environmental protection laws allowed a minority of neighbors to impede a development, even if it had majority support. Again referring to environmental conservation, As noted earlier, environmentalist rhetoric played a key role in Acton’s historical debates about housing development, and furthermore, that the resulting policies had the effect—intentional or not—of keeping people out.

We planners have a term for that, which is sort of descriptive, called a drawbridge mentality. It's like ‘I've moved in, and then I become vocal about changing the zoning bylaws so that nobody else can come in.’ The official argument was about septic capability, environmental resource conservation, and preservation, all of those things. But the real effect—and I don't want to suggest that it was, necessarily the intended purpose, but [it] could have been—[was] to keep people out.”

***

Fischel contends that what Bartl called “the drawbridge mentality” stems from a rational response by homeowners seeking to protect their largest asset. In a 2001 paper, Fischel presented his “homevoter hypothesis,” writing that home values “are the report cards for local government.”

Fischel contends that what Bartl called “the drawbridge mentality” stems from a rational response by homeowners seeking to protect their largest asset. In a 2001 paper, Fischel presented his “homevoter hypothesis,” writing that home values “are the report cards for local government.”

Because homeowners, unlike corporate stockholders, cannot diversify their largest asset - their home - they become active in the governance of municipal corporations. They ‘vote their homes’ in selecting public officials or in plebiscites.

Fischel draws upon his theoretical framework to explain why housing shortages are more acute in the Northeast (where individual towns make land use decisions) and the West Coast (where land use is often the subject of ballot propositions) instead of other regions where the county manages land-use decisions. Fischel says that “local knowledge is critical to sensible land use decisions.” However, he argues that only serving the interests of existing residents creates regional shortages that harm residents and non-residents alike.

Fischel also points out that “zoning is not a single-valued constraint,” but rather, “a complex web of locally generated regulations” that can serve as a force for progress or a force for ill. A 2016 paper by UCLA researchers Michael C. Lens and Paavo Monkkonen attempted to expand on the nuances involved. They found that some policies, such as local project approvals, have a positive association with segregation, while others, such as open space requirements, demonstrate less of an effect. Lens and Monkkonen conclude that constituent pressure “exacerbates the tendency [of local policymakers] to segregate by income,” while state involvement can temper these tendencies.

Other sources also consider the potential barriers posed by local control to meeting regional housing needs and promoting inclusion. Last year’s Greater Boston Housing Report Card led by Northeastern’s Alicia Modestino and the Massachusetts Housing Partnership found that there “is an apparent unwillingness on the part of many cities and towns to participate in developing the diversity of housing we need for our region’s growing population.” When this unwillingness is combined with the legacy of institutional racism and housing segregation, the authors conclude that “established patterns and home rule have only maintained the status quo.”

Concerns around local control and suburban inertia go back decades; a federal report from fifty years ago raised similar concerns. In a report titled Route 128: Boston’s Road to Segregation, the commission described how racial and economic homogeneity creates homogeneity of opinion. The report contends that since local politics are driven by consensus rather than conflict, local officials have little incentive to enact policies that citizens don’t strongly desire, leading to an endless cycle. [9]

Fischel also points out that “zoning is not a single-valued constraint,” but rather, “a complex web of locally generated regulations” that can serve as a force for progress or a force for ill. A 2016 paper by UCLA researchers Michael C. Lens and Paavo Monkkonen attempted to expand on the nuances involved. They found that some policies, such as local project approvals, have a positive association with segregation, while others, such as open space requirements, demonstrate less of an effect. Lens and Monkkonen conclude that constituent pressure “exacerbates the tendency [of local policymakers] to segregate by income,” while state involvement can temper these tendencies.

Other sources also consider the potential barriers posed by local control to meeting regional housing needs and promoting inclusion. Last year’s Greater Boston Housing Report Card led by Northeastern’s Alicia Modestino and the Massachusetts Housing Partnership found that there “is an apparent unwillingness on the part of many cities and towns to participate in developing the diversity of housing we need for our region’s growing population.” When this unwillingness is combined with the legacy of institutional racism and housing segregation, the authors conclude that “established patterns and home rule have only maintained the status quo.”

Concerns around local control and suburban inertia go back decades; a federal report from fifty years ago raised similar concerns. In a report titled Route 128: Boston’s Road to Segregation, the commission described how racial and economic homogeneity creates homogeneity of opinion. The report contends that since local politics are driven by consensus rather than conflict, local officials have little incentive to enact policies that citizens don’t strongly desire, leading to an endless cycle. [9]

[N]o suburban community can be expected to change its racially exclusive policies without the presence of a minority population and cannot gain a minority population without first changing its policies. However, the circle can be broken by decisive action at the State and Federal level.

Congress responded to this landscape in 1968 by passing the Fair Housing Act, which banned racial discrimination in housing. Meanwhile, the state legislature in Massachusetts also saw the need for decisive action, and in 1969, they acted, creating Chapter 40B.

A Primer on Chapter 40B

Drawing upon this one from CHAPA, this one from Acton and this website from the State, along with additional sources as noted.

Drawing upon this one from CHAPA, this one from Acton and this website from the State, along with additional sources as noted.

|

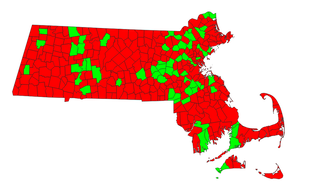

40B is a state statute that seeks to ensure that every town in the Commonwealth has a sufficient supply of affordable housing. It calls on every municipality in the state to set aside at least 10% of its housing as affordable. If a city or town does not meet its 10% threshold, then a developer has the right to build affordable housing without needing the approval of local planning boards.

CHAPA reported in 2011 that, since the 1970s, 40B has been directly responsible for 32,500 units of affordable housing, and over 60,000 units overall. |

A map of municipalities that have met 40B’s 10% threshold. Data from DHCD.

|

What does it mean to be “affordable”

Policymakers generally understand housing to be affordable for a given household if it takes up <30% of their income each month (households paying more than 30% are considered cost burdened). For the purposes for Chapter 40B, housing costs include rent or mortgage payments, but also auxiliary costs such as utilities and home insurance. [10]

Is affordable housing low-income housing?

Not always. Under 40B, a unit can qualify as “subsidized housing” if it is affordable to households earning 80% of the “Area Median Income,” as defined by the federal government based on the size of their household and where they reside. [11]

For example, Acton lies within the Boston-Cambridge-Quincy Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), where the 80% threshold is $67,400 for an individual or $96,250 for a family of four. Combining this threshold with the cost burden calculation means that an affordable 3-bedroom unit could be sold for up to $260,000, or rented for around $2000 a month.

Those income limits are relatively high, and the vast majority of private 40B developments serve buyers and renters at the top of that range. However, other programs exist at the local, state and federal level that target other points on the income distribution. The Acton Housing Authority manages public housing in town, most of which targets households making less than 30% AMI, or at specific groups (such as seniors or people with disabilities). There are also other subsidy programs, such as the federal LITEC grant which targets developments serving households at 60% AMI.

Goal 2 in Acton’s housing production plan makes a point of encouraging development that serves households making under 50% AMI.

What is the Subsidized Housing Inventory

The Subsidized Housing Inventory (or SHI) is an official tally by the state of how many 40B eligible units (both market-rate and deed-restricted—see below) are present in each municipality.

How does a home get on the SHI?

In addition to being inexpensive, a housing unit also needs to carry a deed restriction, which stipulates that the home can only be resold as a 40B unit, and limits the amount of profit that can be made on resale, among other provisions. For example of a deed restriction, see this deed rider, for an affordable condo unit on 99 Parker Street.

There can also be “naturally affordable” housing units, which may have market prices similar to 40B units, but which lack a deed rider and are not listed on the SHI.

Policymakers generally understand housing to be affordable for a given household if it takes up <30% of their income each month (households paying more than 30% are considered cost burdened). For the purposes for Chapter 40B, housing costs include rent or mortgage payments, but also auxiliary costs such as utilities and home insurance. [10]

Is affordable housing low-income housing?

Not always. Under 40B, a unit can qualify as “subsidized housing” if it is affordable to households earning 80% of the “Area Median Income,” as defined by the federal government based on the size of their household and where they reside. [11]

For example, Acton lies within the Boston-Cambridge-Quincy Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), where the 80% threshold is $67,400 for an individual or $96,250 for a family of four. Combining this threshold with the cost burden calculation means that an affordable 3-bedroom unit could be sold for up to $260,000, or rented for around $2000 a month.

Those income limits are relatively high, and the vast majority of private 40B developments serve buyers and renters at the top of that range. However, other programs exist at the local, state and federal level that target other points on the income distribution. The Acton Housing Authority manages public housing in town, most of which targets households making less than 30% AMI, or at specific groups (such as seniors or people with disabilities). There are also other subsidy programs, such as the federal LITEC grant which targets developments serving households at 60% AMI.

Goal 2 in Acton’s housing production plan makes a point of encouraging development that serves households making under 50% AMI.

What is the Subsidized Housing Inventory

The Subsidized Housing Inventory (or SHI) is an official tally by the state of how many 40B eligible units (both market-rate and deed-restricted—see below) are present in each municipality.

How does a home get on the SHI?

In addition to being inexpensive, a housing unit also needs to carry a deed restriction, which stipulates that the home can only be resold as a 40B unit, and limits the amount of profit that can be made on resale, among other provisions. For example of a deed restriction, see this deed rider, for an affordable condo unit on 99 Parker Street.

There can also be “naturally affordable” housing units, which may have market prices similar to 40B units, but which lack a deed rider and are not listed on the SHI.

|

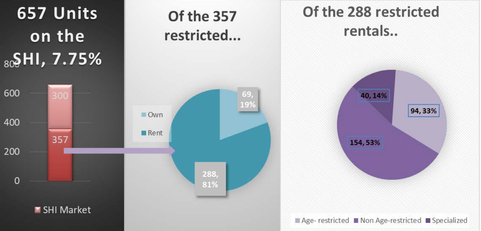

Source: Acton’s Housing Production Plan

|

Are there any exceptions?

In a bid to address shortages in rental housing, 40B has a provision whereby if 25% of the units in a rental development deed-restricted affordable, the entire development qualifies for a 40B permit, and all units (market rate and affordable) are included on the SHI. Just under half (300/657) of Acton’s SHI eligible units are market-rate rentals, and the percentage is similar statewide. |

What is Safe Harbor?

Safe Harbor gives communities making progress towards their affordable housing obligations, allowing communities who have submitted a plan to reach their 10% goal (in the form of an HPP) and who are making adequate progress towards that goal to reject 40B developments—in essence to be exempt from 40B zoning overrides—for a set period of time. Safe harbor periods (and HPPs) last for a duration of five years.

Safe Harbor gives communities making progress towards their affordable housing obligations, allowing communities who have submitted a plan to reach their 10% goal (in the form of an HPP) and who are making adequate progress towards that goal to reject 40B developments—in essence to be exempt from 40B zoning overrides—for a set period of time. Safe harbor periods (and HPPs) last for a duration of five years.

Part 5: Fulfilling 40B

“Neither one of us would want to be in a position of concluding that African Americans can't afford to live here, because African Americans are poor,” starts Nancy Tavernier, longtime resident and chair of the Acton Community Housing Corporation, speaking on behalf of herself and Bob Van Meter, another committee member of the ACHC. We’re sitting around a conference table on the first floor of the library, and Nancy’s showing us a flyer with “ACTON VALUES DIVERSITY” emblazoned across the top. The flyer is part of an outreach campaign by the ACHC, a town committee tasked with supporting the development of affordable housing.

“That's not what we're saying at all.” Tavernier emphasizes, “But we all understand they've been deprived of opportunities for decades, and therefore they are limited by what they can afford. I don't think there's much discrimination going on anymore. Maybe I'm naive. But it's now a question of what can you afford?”

Tavernier and Van Meter have both been affordable housing advocates for quite some time, and Van Meter has managed affordable housing projects himself as a project manager. Over the years they’ve seen Acton make a fair bit of progress.

The latest Subsidized Housing Inventory credits Acton with 657 units, representing 7.75% of its housing stock. 357 of these units are deed-restricted as affordable, while the other 300 are market-rate units in 40B developments.

This represents a massive improvement. According to, Tavernier, the town’s affordable housing had been “stagnant” for 20 to 30 years at the end of the 20th century; as late as the mid 2000s, SHI units made up only 2% of Acton’s housing. Much of the increases since then have been from the Avalon development in North Acton, which was first permitted in 2006 with an expansion permitted this past year. But even outside of Avalon, Tavernier said that interest from developers in 40B projects has “definitely picked up.”

Statewide, Chapter 40B has helped to create over 60,000 rental and homeownership units, about half of which are deed restricted, according to a 2011 estimate from the advocacy group CHAPA. The impact of 40B has been concentrated in desirable suburban towns, where the demand is particularly acute, and the supply is particularly constrained (due in part to local zoning).

While 40B has served its purpose in these respects, it has not done so without controversy. 40B has often been maligned by local officials and residents alike, who argue that it deprives towns of self-governance and creates a boon for developers. [12] The law survived an attempted repeal at the ballot box in 2010 (Acton narrowly voted not to repeal).

In addition to the anxieties around local control, many people have also questioned 40B’s effectiveness, especially considering the state’s ongoing housing crisis. Similar questions exist in Acton regarding the limits of 40B.

For one, home prices in Acton have continued to rise. According to the HPP, the number of homes in Acton that sold for $800,000 or more in 2010 was 22 compared to the 36 sold in 2019. Simultaneously, the number of homes sold in Acton for under $500,000 dropped by nearly 50%, from 84 homes in 2010 to 45 in 2019, which represented 19% of all home sales in 2019.

On the other hand, residential development in Acton is also constrained by many tangible and intangible factors. As described in the HPP, the remaining land for development, excluding wetlands and other environmentally protected land, is 2,200 acres. “Based on 2008 data, approximately 1,800 new housing units could be constructed under current zoning, contributing an additional 22% to Acton’s housing stock. Most of the available land for future housing development is composed of fairly large parcels that must be subdivided in order to leverage its development potential.” Additionally, groundwater protection laws regulate development to ensure that “all residents served by the District will be able to access sufficient clean water for as long as the Town exists”

40B was never intended to be a silver bullet, addressing all of the barriers outlined above. But 40B specifically targeted political constraints, and some of those have persisted as well. “I've talked to real estate developers who tell me they basically don't do 40B developments because they're worried about lawsuits,” explains Bob Van Meter, who himself has managed affordable housing developments as a developer, “[s]o if they're going to develop rental housing, they will go to a community like Lowell where they're more accepted, and do it there, where the city may welcome the development. So you don't necessarily have all of the real [estate] development community competing for sites in places like Acton because they say ‘well, it's too much trouble.’”

In addition to lawsuits, residents and officials have other potential means of impeding a 40B development. The proposed apartments on Powder Mill Road were originally supposed to cut across the Acton-Maynard line, but many Maynard residents were leery of granting it sufficient sewer capacity, and the project now resides fully in Acton. Elsewhere, A proposed development on Piper Lane received fierce opposition from a neighborhood group. The South Acton Neighborhood Association campaigned against the project for years on a litany of fronts ranging anywhere from road safety, and public health to environmental conservation, historic preservation and architectural design. Their efforts were ultimately successful, as the developer is on track to sell the lot to the town, after years of bureaucratic battles. SANA insists that it does not oppose 40B projects in general, but its efforts in this specific case nonetheless illustrated the limits of Chapter 40B in overcoming local inertia.

And while 40B grants regulatory exemptions on a project-by-project basis, changing the regulations themselves is a herculean task, especially since Massachusetts requires changes to the zoning bylaw to receive a two thirds supermajority at town meeting, instead of the usual simple majority required of other motions and of land-use decisions in other states. In 2017, Governor Charlie Baker proposed a bill to require only a simple majority for certain votes like reducing lot sizes or allowing in-laws apartments, making it easier in theory to enact reforms.

The Baker administration argues that reducing the threshold for action will help increase the housing supply and help to address what Baker considers a housing “crisis.” But as a report from Commonwealth Magazine detailed, the bill faces criticism both for going too far and not far enough. Some progressives and activists have criticized the bill for not placing enough emphasis on affordable and low-income housing, leaving the door open for upscaling, displacement and gentrification. Meanwhile, some towns have argued that they should be exempt, because they have met the state minimum standards under Chapter 40B. Baker continues to advocate for his “Housing Choice” bill, but even if the legislature eventually signs on, the bill’s impact will be marginal, since in most communities with restrictive zoning, the practice enjoys widespread popularity.

Chapter 40B has made a lot of progress towards housing affordability, even 40B places a burden on towns to be proactive to a certain extent, as Acton’s history through the 1990s aptly demonstrates. But the need for proactive management is magnified once a town meets its 40B responsibilities, as Acton is on track to do.

Part 6: What's Next?

By adopting its recent Housing Production Plan, Acton is eligible for a “safe harbor” reprieve from the 40B zoning override process. Furthermore, if Acton carries out its commitments under the HPP, it is expected to cross the 10% 40B threshold for the first time in its history. This elicited a sigh of relief from some residents at the January public forum, marking the end of a decades-long intrusion from the state. For others, this marked the start of a new chapter.

As Selectman Jim Snyder-Grant later noted, this is the first time Acton’s been given a choice, and an ability to be proactive. “We've had housing production plans before, but [because of 40B] this is the first time we've had [an HPP] where the selectmen are now in a position to actually say yes or no to affordable housing projects...This will be the plan that lets proponents and opponents of affordable housing, say, look, you said you wanted this or you said you didn't want this. So, you know, give us permission.”

Safe harbor allows Acton to build more thoughtfully and to be proactive, tailoring projects to needs identified by the community. But this also requires the town to be articulate about it’s goals, and to balance the desires of various stakeholders; for boards and committees in town government, even hearing from everyone can be a hurdle.

Researchers at Boston University looked at public meeting minutes in communities around the state and found that attendees at public hearings like the HPP forum are older, less diverse, and more likely to be homeowners than the community as a whole. The researchers then explored how this translates into greater community hostility towards development at public hearings than is evident through other measures like how the town voted in the 2010 40B referendum. [13]

Housing for All wants to change the typical dynamics of the public comment period is Housing for All. Composed of housing advocates from Acton and surrounding towns—including Tavernier and Van Meter the ACHC—Housing for All seeks to be a more “flexible” organization than the official ACHC, focusing on education and advocacy. Safe harbor allows Acton to build more thoughtfully and to be proactive, tailoring projects to needs identified by the community. But this also requires the town to be articulate about it’s goals, and to balance the desires of various stakeholders.

The town has already taken some creative measures towards balancing the desires of residents to protect the environment and preserve open space with the desire to increase housing supply and affordability. For example, the town started to implement “cluster zoning” (based on the 2012 master plan) which allows developers to build more homes in a given area if they “cluster” the homes together and preserve the surrounding open space.

This balance between housing needs with preservation dominated the conversation at the public forum. The first audience question at the public forum concerned how much to focus on buying and deed-restricting existing condo and apartment units (especially “naturally affordable” units) in lieu of new development. Further analysis in the HPP concluded that while buying down condo units could be part of a policy package, rehabilitation alone would not be sufficient to reach 10%, and waiting for low-priced condos to come on the market would limit the speed by which such a program could proceed.

Of course the accounting maneuver of reclassifying a naturally affordable unit as a deed-restricted one does nothing to create more affordable housing, even if it is arguably a more accurate representation of the town’s affordable housing stock. However, some proponents of rehabilitation, such as longtime local activist Terra Friedrichs, have proposed using these naturally affordable units to serve a poorer segment of the population than the 80% AMI typical of 40B development. [14] In the final production plan, the first goal mentions reaching 10% “primarily through rehabilitation or reuse of existing buildings, where feasible” while the second encourages more affordable housing production targeted at households making under 50% AMI. Other goals included environmental priorities—promoting conservation via cluster zoning, and sustainability through a focus on walkability—as well as an effort to support “community education” around fair housing issues

One thing that came up sparingly in the document and the conversation around it was any discussion of race.

“I don't think for one minute any of us and most of the public who participated even thought that we were ignoring racial diversity,” Nancy Tavernier replied when asked for comment. “I for one assume any production of affordable housing offers an opportunity for diversity of all types from racial to economic. I think everyone supports Fair Housing which focuses on eliminating the barriers to more housing.”

In her reply, Tavernier also highlighted the HPP’s “planning and political context” section, which explains that “[p]ublic input points to a strong preference by some residents to limit growth, citing the benefit of open space conservation.” The town writes however, that restricting development “has an unintended side effect of maintaining the economic and demographic constituency currently in place.”

The HPP goes on to contend that development and conservation “are not mutually exclusive” but two essential ingredients to a vibrant and sustainable community that should be thoughtfully balanced.

Creating a shared vision of town character, and achieving that vision is important work. Modifying zoning bylaws requires two-thirds vote at Town Meeting – a high bar. Zoning is often a difficult subject to describe to Town Meeting, and there is always going to be neighborhood opposition to any development proposal. It is incumbent on the Planners and Board members to educate the public on valid Town goals so that a general understanding of the benefits to the Town as a whole are communicated.

While the HPP itself is rather diplomatic, the town’s response log for HPP comments put the matter more directly in response to a comment by Jim Snyder-Grant:

While [an] admirable goal, broadening racial diversity was not identified as a town imperative.

|

Part 7: "No Justice, No Peace"

It’s now a warm, summer’s day in the beginning of June, and amidst an early bout of Massachusetts humidity, a new public forum emerges, trading the elementary post-it notes of the January forum for cardboard signs and fists of solidarity at Kelley’s Corner. The crowd no longer dons the down jackets and mittens of the winter gatherings, instead warmed by a setting sun and the heat of the other mask-clad protesters. It takes little advertising to gather this crowd—simply a single Facebook page and a clear rallying cause: Black Lives Matter. |

A June rally at Kelley's Corner in support of racial justice

|

On May 25, Minneapolis police choked George Floyd, a Black man, to death in broad daylight. Floyd’s murder sparked widespread protests against police brutality and systemic racism, including in Acton-Boxborough. The demonstrations at Kelley’s Corner seemed a natural extension of the general sentiment of liberalism and allyship that the community seeks to convey. On top of healthcare inequalities exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the repeated and unchecked actions of law enforcement against Black Americans provided the everyday suburbanite with an explicit manifestation of the racism so casually ingrained in our society.

The suburbs have always been a place of escape from issues of inequality, [15] a place where cul-de-sacs and gated communities and white picket fences create a plane of separation between a person and those issues deemed “urban” and “unsightly.” Attempts to preserve “rural character” and the suburban lifestyle thus not only targeted “unsightly” apartments, but often “unsightly” people as well. Consciously or not, these motives helped to drive white flight following World War II, and they persist today in the lack of Black and Latinx representation in these towns. That is, after all, the founding principle of the suburbs—division.

“You combine [the history of redlining] with the zoning scheme. And the fact that Black people and families generally started out at a disadvantage to begin with—it just perpetuates” Roland Bartl summarizes. "And I think a lot of times, I want to believe that in Acton, a lot of these things were not done at the forefront of people's conscience. It was just something that people did and you didn't even think about it. You know, and then the movers and shakers… But they thought it was OK. They thought that was the way you managed your community.” [16]

In her book Don't Blame Us: Suburban Liberals and the Transformation of the Democratic Party, Dr. Lily Geisemer explores the contours of suburban politics by focusing on the region around Route 128. As she explained to WBUR in 2016, “[t]he closer and closer you get to people’s property values, their tax rights and their children’s education, their politics become less progressive.” It’s quite clear who has been excluded from the town’s narrative. Three months after Mr. Floyd’s death, and nine months after the incident at Merriam, the solutions remain to be seen.

Systemic racism is part of American history, and in this, Acton is not alone, or even exceptional. Exclusionary zoning continues to be the norm, up and down 128. Many Massachusetts towns still fall short of their 40B targets, as the state’s housing crisis continues to grow. And the legacy of redlining still reverberates across the country, creating inequities in housing, healthcare and policing that perpetuate themselves in turn.

There’s a motto that arose from the environmental movement—think globally, act locally. Acton takes pride in its global mindset. But as we witness a second March on Washington mirrored in weekly Kelley’s Corner gatherings, there is growing pressure to act.